We know that stories play a crucial part in developing children’s understanding of the world. That begins with simple nursery rhymes, such as Jack and Jill or Humpty Dumpty, that have a straightforward structure of a beginning, middle and an end, characters with whom we can empathise, emotions that we understand and whose failings and actions have consequences. The story of A Midsummer Night’s Dream has more well developed characters and a complex plot that twists and turns, but the elements are essentially the same. We are invited into a secondary world and explore it through what the characters do and say to one another. The world in A Midsummer Night’s Dream appeals to our imagination in that it is similar to, and yet very different from, our own. A fairy world existing in shadows alongside the world of humans is not uncommon in children’s literature, so they would have no difficulty in accepting this scenario. We all know that strange things happen in enchanted forests, especially at night.

Professor Barbara Hardy in Poetics of Fiction (1968) explained the importance of narrative in our lives:

We dream in narrative, day-dream in narrative, remember, anticipate, hope, despair, believe, doubt, plan, revise, criticize, construct, gossip, learn, hate and love by narrative,. In order really to live, we make up stories about ourselves and others, about the personal as well as the social past and future.

Shakespeare wrote plays to be seen and heard by adults, but his stories are accessible to children if they are told clearly and with care for the needs of reader or listener. This has been be done in a number of ways from the elaborate Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare to the visually dynamic Graphic Shakespeare. As we wanted to tell the story for children aged 4 to 8, we chose to do that through an illustrated picture book, a medium with which they would be familiar. Sharing a picture book can begin well before children can read and that prepares them for reading the story for themselves when they can. Hearing the story is important in establishing reading readiness. Hearing the story read aloud, preferably several times, establishes knowledge of the characters and the plot. Hearing the syntax and vocabulary creates the setting and atmosphere for the listener. Reading the illustrations reinforces and extends all these aspects of the story. At a later stage the illustrations support children when they come to read the book for themselves.

Meeting Shakespeare at an early age and through a picture book lays the foundation for reading stories by others. Many writers have based stories on Shakespeare’s plays, just as Shakespeare borrowed from other writers for his work. Malorie Blackman’s Noughts & Crosses and Joan Lingard’s Twelfth Day of July explore the same theme of teenage love thwarted by racial, social and religious barriers and prejudices. There are many other examples when the same story is told through music, song and dance. Shakespeare’s tale of Romeo and Juliet, which he adapted from another story, has been retold in our times in different media and for a different audience. Shakespeare is an established part of the cultural experience of this nation’s literary heritage and his work has been absorbed into other cultures across the world. Having Shakespeare in your reading portfolio connects you to others who share the same interest. The earlier we can offer it to children in this form and through well-edited scripts, the less intimidating it will be when they encounter it in the more formal setting of English Literature lessons in secondary school.

Shakespeare’s plays explore the human condition and invite us to make judgements on the characters. When I shared The Tempest with a class of 30 six-year-olds, a child asked me if Ariel could never die because unlike the other characters, he was not mortal. I was stunned by his perceptive question and commented to the teacher about it. He was a non-reader of words and struggled with reading and writing, but he understood how Ariel was not like him and could live for ever. He believed that the character existed and the story and the illustrations had fired up his curiosity and his thinking. Other children commented that Prospero forgiving his brother was the right thing to do. These philosophical and moral dilemmas, embedded in our re-telling, are crucial to explore with young children. Developing critical thinking does not begin with academic study, it begins with asking questions about why people behave in certain ways and what influences their actions. Why does Oberon want the changeling boy? Is it because he needs an extra pair of hands in his gang? Or does he not want Titania to show affection and commitment to someone other than him? Is it fair that Egeus can stop Hermia marrying the man she loves? Is it right to use underhand methods to get what you want? These questions will become an essential element of study when students study the play in formal educational settings in secondary school, and the question of misogyny, revenge and forgiveness might be on their GCSE examination paper. When children have the opportunity to perform in or see the play, they will be less anxious if they have first met the story through an enjoyable experience of a beautifully illustrated picture book. I know of Primary teachers in this country and in the USA who have used The Tempest picture book to devise a programme of cross curricula work for their pupils and a school in London created a whole school production, involving every child from Early Years to Year 6. I hope A Midsummer Night’s Dream inspires other teachers to do the same.

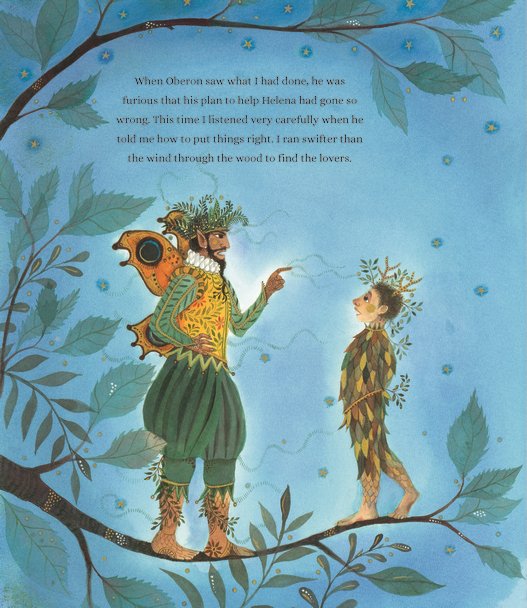

Reducing the story to fit into 28 pages, and taking into account the illustrations that had not yet been created, had its challenges. There was much re-phrasing and editing at the various proof stages to ensure pictures and text matched and that the words did not collide with objects or characters in the illustrations. When I retold The Tempest, I could leave out certain characters and events, such as Trinculo and Stephano and Caliban’s plot to kill Prospero, without losing the animosity between them, but the interlacing of events and characters in A Midsummer Night’s Dream made that impossible. Without Bottom and the Players, you cannot have the Queen of the Fairies falling in love with an ass and Oberon getting his revenge on her. Without the lovers you would not have the chaos and confusion after Puck administers the potion to the wrong Athenian and which creates the comedy around the lovers. My aim when retelling the story is to make it clear who these characters are, what they want and what they were prepared to do to get what they want. Jane worked on the text I had written to create the different settings and to dress and visualise the characters’ bodies and faces to make them fully rounded people. I wanted to include words from the play when I could work them in. I would have loved to have done more of that, but the limited word count did not allow that. If I could not use direct quotations such as ‘Lord, what fools these mortals be ‘, I tried to blend them into the text. Puck is described as a ‘merry wanderer of the night’ and I changed that to Puck telling the reader that he ‘merrily wanders’. From my experience of working with children and students of all ages, they love to hear, and speak, Shakespeare’s language. A book that does not include Shakespeare’s words, where it can, is missing some of the gems of his work and is denying children the opportunity to wrap their tongues around some thrilling words. They do not see Shakespeare’s vocabulary as difficult or a different language – if they can manage Diplodocus and Tyrannosaurus Rex, Caliban, Prospero, Titania, Oberon and all the other exciting names offer them few problems.

I felt it was important to have a narrator with whom children could identify and who played an important part in the story. It was easy to decide that for The Tempest: I would retell the story from Ariel’s perspective as he/she saw everything that happened on the island, could also tell the reader about Prospero’s previous life in Milan and, for me, is the most endearing character in the play. It was the same with Dream. Puck is the happy go lucky, eager to please character who never means to do harm, but whose carelessness causes havoc. Most of us wish we had listened more carefully to instructions or have caused problems by completing a task without first checking what it was that was required. Children know that feeling well. As a spirit Puck can move between the human world and the fairy world, swiftly and silently. He has the best part in the story. I think some children would quite like to be Puck, maybe some adults too. I found it much harder to choose the narrator for our third book, Twelfth Night. I won’t tell you who I settled on. Who would you choose?

Thank you to Georghia and Walker Books. You can also read our interview with the book’s illustrator Jane Ray here

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is available from The Shakespeare Bookshop or our online shop

Illustrations © 2021 Jane Ray