Some of the early books in the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust archives give invaluable insights into the attitudes towards music in Shakespeare’s time. One of the most fascinating books in the collections is The Praise of Musicke, as it helps to explain just how important music would have been to Shakespeare and his contemporaries, and why.

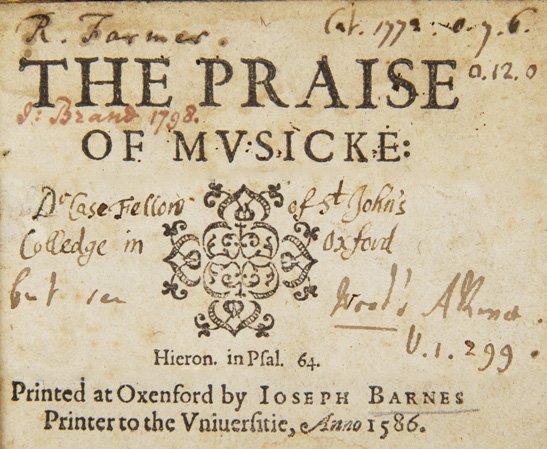

The Praise of Musicke is attributed to John Case and dedicated to Sir Walter Raleigh. It was published in Oxford in 1586, approximately five to ten years before Shakespeare’s first play, The Comedy of Errors, was written. The book is an extended essay in praise of music's virtues and importance. It explores the widely held contemporary belief that music was fundamentally woven into the fabric of the universe, and was essential for it to function properly.

This idea was rooted in the teachings of classical authors such as Pythagoras and Plato, and later classical writers including Boethius. The central idea was that the universal is formed of mathematical divisions, which resonate with each other to create a “universal harmony”. This harmony is referred to as “the music of the spheres”, or musica mundana. Shakespeare’s contemporaries believed that this was mirrored in the human body and soul, a microcosm of the universe, as musica humana. An imitation of this harmony could be produced with musica instrumentalis, by playing musical instruments. (For more information on this, read Shakespeare and Music, by David Lindley.)

Both John Case and Shakespeare reference these different forms of music in their work:

"There's not the smallest orb which thou behold'st

But in his motion like an angel sings,

Still quiring to the young-eyed cherubins;

Such harmony is in immortal souls;

But whilst this muddy vesture of decay

Doth grossly close it in, we cannot hear it."

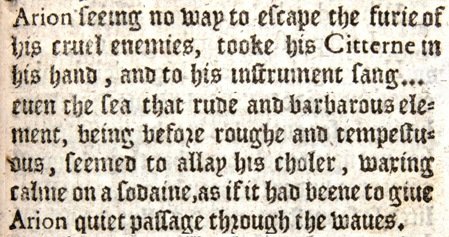

The power of music is a hugely important theme within Shakespeare’s work. There are many different facets to this power: among them are music's effect on animals, and on nature and the elements more generally. There are interesting parallels in Case and Shakespeare's works on these effects, which I’ll briefly explore here. The first example is of music’s power to calm the sea. While this depiction is perhaps a more poetic than realistic portrayal of music, its inclusion by both writers shows how popular the image was with Shakespeare’s contemporaries, and how familiar it would have been:

"Thou remember’st

Since once I sat upon a promontory,

And heard a mermaid on a dolphin’s back

Uttering such dulcet and harmonious breath,

That the rude sea grew civil at her song,

And certain stars shot madly from their spheres

To hear the sea-maid’s music.'

A Midsummer Night's Dream, 2.1

The second example is music’s effect on horses. While their reaction to music is very different in Case and Shakespeare’s accounts, it shows that Shakespeare and his contemporaries believed that music could provoke a range of different reactions, including rage, melancholy, joy and tranquillity, even in animals:

"Do but note a wild and wanton herd,

Or race of youthful and unhandled colts,

Fetching mad bounds, bellowing and neighing loud,

Which is the hot condition of their blood;

If they but hear perchance a trumpet sound,

Or any air of music touch their ears,

You shall perceive them make a mutual stand,

Their savage eyes turn'd to a modest gaze."

The Merchant of Venice, 5.1

Music, then, was seen as something with universal importance and significant power. It did matter greatly to Shakespeare and his contemporaries. As well as animals and the elements, Shakespeare and Case both explore music’s power over the emotions, thoughts and actions of people in far more detail.

For more information on Shakespeare and the music of the spheres, click to watch Bill Barclay's lecture "Muse on Fire".

(The Praise of Musick can be accessed on request in the Trust's Library and Archive Reading Room.)