In my previous blog I explored Rebecca Dering’s views on women’s suffrage in the early twentieth-century. In one of her letters she pleads with her friend ‘Don’t please encourage women’s suffrage!’ and because of this it's possible to jump to the conclusion that Rebecca was firmly against women’s political engagement. However, if we delve a bit deeper into her family connections we are forced to rethink.

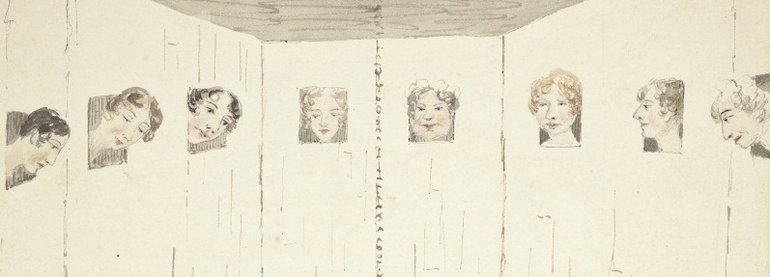

As 2018 is the centenary of women’s suffrage, a lot of effort has been put into exhibiting British women’s political history. A key artefact from this movement, and a cornerstone of the 'Voice and Vote' exhibition at Westminster, is a sketch drawn by Rebecca Dering’s aunt and found in one of Rebecca’s own sketchbooks. Lady Georgiana Chatterton, the aunt and companion Rebecca travelled and lived with for much of her life, created this watercolour sketch of several women sat in an old attic space above the House of Commons. The space was known as the Ventilator and was the only place women could hear and partially see what was happening in the House of Commons below them by sticking their heads out of the small windows. This was a radical act at a time when parliamentary reporting did not exist for fear it would stifle free debate.

Lady Georgiana Chatterton led an interesting life in her own right. Georgiana enjoyed the early years of a socialite and ‘came out’ to society in 1824 in the presence of George IV. She became a prolific and wealthy author in her lifetime, writing fiction and travelogues such as her book ‘Rambles in Southern Ireland’, which sold out within weeks of being published in 1932. After the death of her first husband, Sir William Abraham Chatterton, she married Edward Dering in 1859, also a novelist. The story goes that Edward was actually asking Georgiana for permission to marry her niece Rebecca, but having misheard she believed the proposal was for her. Edward was far too gentlemanly to explain otherwise and married Georgiana who was almost twice his age. The couple lived in Baddesley Clinton with Rebecca and her husband Marmion Edward Ferrers, in a rather bohemian fashion, indulging in their respective arts and wearing seventeenth-century dress. Georgiana died in 1884 at the age of 69.

The sketch was unearthed by an archivist from the Dering collection at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in 2015, and its significance was realised after he asked on Twitter if anyone could identify the image. It was found in the back cover of one of Rebecca Dering’s sketchbooks and we can be almost certain this sketch was by Georgiana, and not Rebecca, as it was alongside two tickets to Westminster Hall for 11th July 1821, nine years before Rebecca’s birth. We can then also assume that Georgiana herself observed the House of Commons from the Ventilator.

The sketch is a watercolour, depicting eight women with their heads stuck out of the windows of the Ventilator looking down on the Members of Parliament in session. We cannot know if this painting was done in situ, though this is unlikely as the space was known to be stuffy and uncomfortable. However, the sketch may be depicting Georgiana’s viewpoint when she was looking out from the Ventilator. She is able to see the other women also looking out as it was a rounded structure, with no more than fourteen ladies able to sit or stand all the way around. This can be seen more clearly in another sketch of the structure by Frances Rickman in 1834. We are also able to see the chandelier that they were above, and the public galleries in the House of Commons where women were not permitted to sit. The Ventilator was only in use until 1834 when a fire destroyed St Stephen’s Chapel, after which a Ladies Gallery was built.

We could assume that it was largely elite women who had the opportunity and money to travel to Westminster and acquire tickets to enter the House of Commons, as Georgiana did, but because this political space was unofficial and largely overlooked there were no rules as to who was permitted. It is thought that there was some diversity of backgrounds present for the debates. Some were visitors to London who wanted to see a debate while they were there, while others were family or servants of the MPs.

This brings us back to the issue of what were women’s opinions on their own role in British politics before their enfranchisement. What did this keepsake signify to Rebecca? Was it a memento of her beloved aunt? Did she even realise what the drawing depicted? As with all historical conundrums we can never know for sure, so what should we do with the evidence that we have? Many historians want to take what evidence and artefacts remain from the past and apply them to our world today; but is it right for us to take this sketch and make it a centrepiece for celebrating women’s suffrage when the artist may not have believed in it herself?

We will never know if or how Rebecca’s and Georgiana’s political opinions differed, but both Rebecca’s letter and Georgiana’s sketch show us how even without the vote women were able to engage politically through informal means, whether that was listening in to parliament from a ventilator or persuading tenants to vote for a certain local MP. Women have found ways and means to have an influence in politics for centuries and gaining the vote was finally a formal recognition of a place for women in politics.