Creating a display for our incredibly successful Winter School course for Leisure Learners gave me the opportunity to see a new side to our early printed book collection: the hidden life of books as evidenced by their marginalia. Where have these books lived? Who bought them? How were they used? Which bits did their previous owners enjoy? What part did they play in someone’s life? One of the guest lecturers at this year’s Winter School was Professor Emma Smith from Hertford College, Oxford. She gave a lively, insightful and entertaining lecture on her new book, Shakespeare’s First Folio: four centuries of an iconic book (Oxford University Press, 2016). This vividly demonstrated the ‘lives’ of First Folios and their use for commonplacing, writing practice and much more, culminating in possibly the best use of Powerpoint I have ever seen when a giant possum loomed out of the screen. (You will have to read her book to find out why!)

I found many interesting examples of traces left by readers of long ago in our own collections, each telling us something about them, their lives and their relationship with the printed word.

First we have the reader using the margins of the book to demonstrate their love of (or at least dedication to) learning. This copy of John Kitchin’s Le court leete et court baron (a kind of ‘Dummy's guide’ for court stewards wishing to learn about the running of manorial courts) of 1598 has been used (presumably by a child) for alphabet practice. Every space on this endpaper has been diligently filled with letters.

Many books contain inscriptions which seem to demonstrate the pride the owner feels in owning the book. Our copy of Sir Patient Fancy, by Aphra Behn carries the declaration “Mrs Anne North her book”. Such notes seem to suggest that the owner intends to keep and cherish the book. Was she a newly-wed, particularly keen to sign herself Mrs Anne North?

John Payne Collier (literary editor and forger – google ‘Perkins Folio’ if you want to know more about this!) has added an interesting note to the front of one of our Third Folios. He writes retrospectively about his purchase of the book and the part it has played in his life, reconciling himself to the disappointment he first felt upon discovering that it was a Third Folio and not a First as he once believed, as it is after all a Folio, and the only one he has ever owned.Some annotations demonstrate how love of the contents has prompted former owners to their own creative endeavours:

This copy of Massinger’s The Emperor of the East has inspired an amazing illustration of its eponymous hero. How has this image shaped the mental image subsequent readers have had of the Emperor?

Our copy of John Davies, The original nature and immortality of the soul, 1697 has a poem in the back, showing former owner, John F.’s love for Shakespeare and his humble attempt to write a verse himself.

The greatest man that this world knew Was William Shakespeare who tamed shrew He lived and wrote immortal plays Which will e’er speak till endless days And so for John this once did try To imitate so had in shy By writing of Immortal soul So try and reach Fame’s earthly goal. J.F.

Marginalia also builds up a sense of relationships of the past. Some books have clearly been gifts, such as this Second Folio, given to the actress Helen Faucit (Lady Theodore Martin), by Reginald Cholmondeley. Both were interesting figures of the time. How he must have cared for Helen Faucit to give her such a gift. This connection between them and their friendship, although documented elsewhere due to their fame, is also immortalised on this page.

He loved his friends, Browning and Lady Martin among them, but he hated the sight of a stranger and indulged his eccentricities and an easily triggered temper. He collected birds of paradise and was a well –informed naturalist, many of his specimens being in the Museum of Natural History . His hobby suggested the subject for Millais’ The Ruling Passion, which portrays and aged invalid lying on a couch, fondling a tiny bird and surrounded by deferential relatives.

— (Taken from Learned Lady; Letters from Robert Browning to Mrs. Thomas Fitzgerald, 1876-1889)

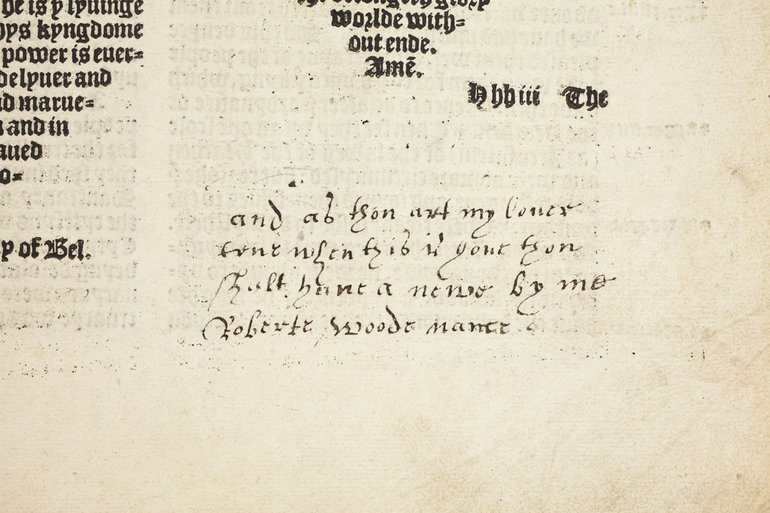

Not only have former owners perpetuated themselves in these pages by what we might now consider ‘graffiti’, they have also recorded and preserved forever their friendships and loves, through dedications, and through more overt declarations. Our copy of the Cranmer Bible contains a little poem under The Prayer of Manas (part of the Apocrypha):

and as thou art my lover true when this is your thou shalt have a newe by me Robert Woode name

Robert Woode has used the margins for handwriting practice and declarations of ownership elsewhere in the book. Is he writing this for his lover to see? Or is this something he plans to say to her? Or is it just a way of expressing and recording his own feelings in anticipation of his marriage?

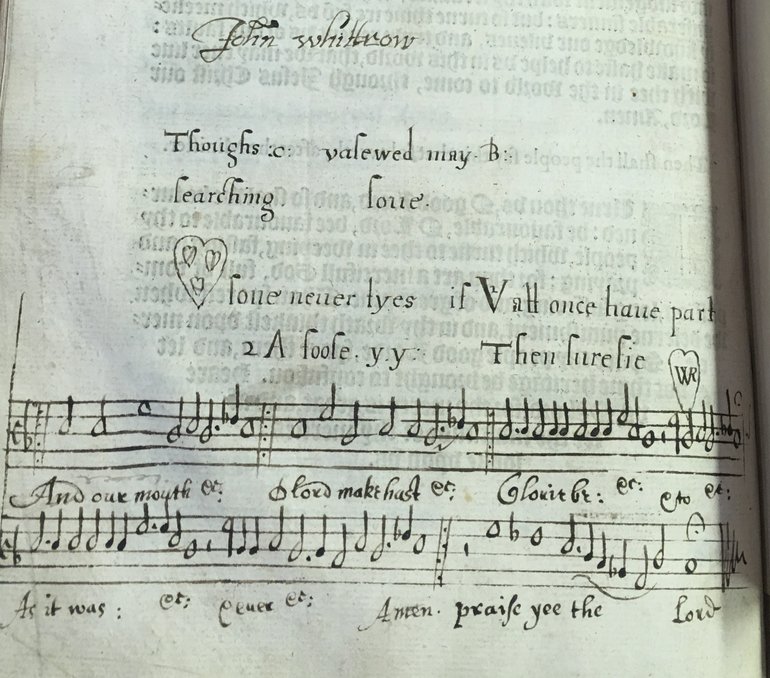

This Book of Common Prayer from 1598 is bound with two psalm books. As well as freehand musical notation this page has some rather cryptic annotations, including a number of hearts and a heart enclosing the letters ‘WR’. Who was ‘WR’? Was this the tentative expression of a love not yet declared by a reader unable to suppress their feelings? We will never know!

Like Orlando in As You Like It, bedecking the trees with verses and carving on every tree (Act 3, Scene 2), it seems that the owners of these books have felt compelled to express their love for perpetuity in the pages of their books.

There is something at once fascinating, vertigo-inducing and poignant about the fact that the thoughts, doodles and loves of these people have long outlived them, preserved forever as long as the books survive. Whatever else may remain of them, we have this tiny window into these moments they shared with their books. These notes and drawings have since become part of the book and the experience of reading it for every subsequent reader, subtly altering the text and adding a new dimension to it.

There is something special about sharing a favourite

book, play or poem with someone you care about, opening up your thoughts and

feelings to another person through the medium of literature. Will you be giving the gift of a book this

Valentine’s Day and writing a message in the front? Or slipping a treasured card or letter into a

book for safe-keeping? Whilst we would

never advocate writing in books, history shines a different light on this

practice – one I

hope the availability of online books and cheap paperbacks never renders

obsolete. These examples seem to suggest that the clichéd idea of songs and poetry that 'love is everlasting' or 'love is what survives' is true, at least in the world of marginalia. I doubt John Woode and 'WR' could ever have expected their doodles being shared with the world in this way.

Find out more about our courses for Leisure Learners, or visit our Reading Room if this blog has piqued your interest!

Books:

The original nature and immortality of the soul

With special thanks to our volunteer Phil Spinks for his help with transcribing the trickier bits of marginalia.