Let’s imagine, in the dark, backward abysm of time, that Heminges and Condell decided not to publish Mr William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories and Tragedies on 8 November 1623.

Let’s imagine, that when their other great ally and shareholder, Richard Burbage, dies in 1619, they lost the heart and the energy to continue with the project.

Let’s imagine, even at the last, that the death of their ‘beloved countryman’ Shakespeare’s wife, Anne, throws the whole project up in the air, and it grinds to a stuttering halt.

Or let’s imagine that the monies Shakespeare left to his crew, for mourning rings, were not the spur to prick the sides of their publication intent, but just that: a souvenir, a memento, and touchstone of friendship and love. Let’s imagine, they didn’t buy rings at all: they went shopping or to the tavern.

So, let’s imagine we have no First Folio:

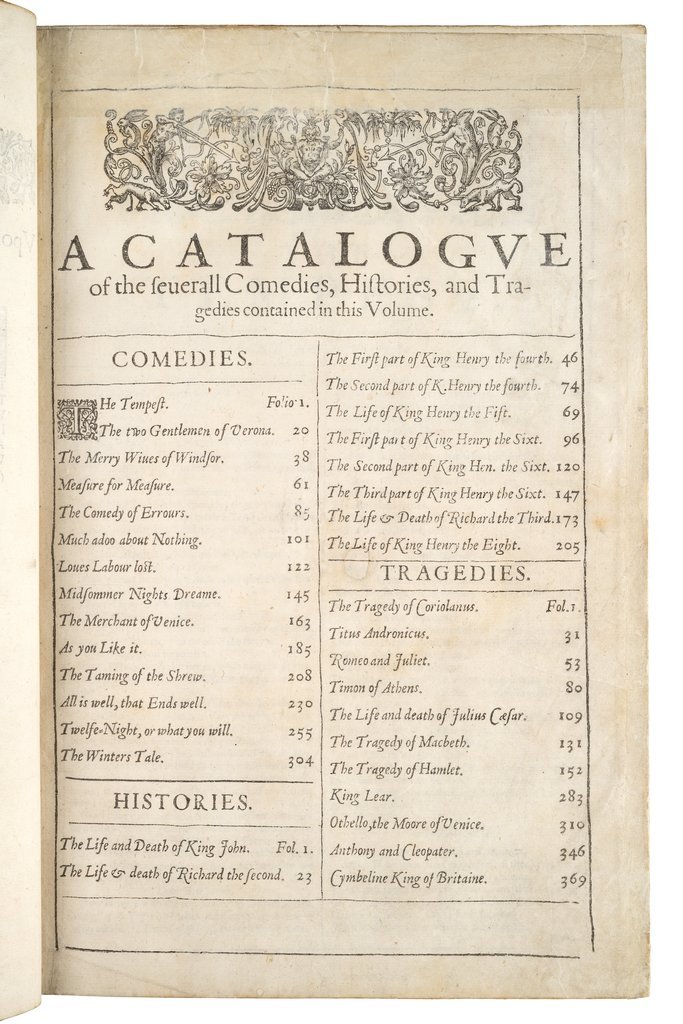

Much has been made about the importance of the 18 previously unpublished plays: a literary life without Macbeth, or Antony and Cleopatra, Twelfth Night, Julius Caesar seems unthinkable? What would we say about sleep if we didn’t know that it knits up the ravelled sleeve of care? What about dying Egypt and the burnished throne? What about the dogs of war or the whirligig of time? How might we have navigated life not knowing that all the world was a stage, and men and women, merely players? How would we have managed funerals without fearing no more the heat of the sun? In fact, how would we have left the house without knowing that life is a tale told by an idiot signifying nothing? Even now, like Macbeth, this horrid suggestion is making our heart knock at our ribs and our hair ‘unfix’ from our skulls.

So, the loss of those 18 plays is true (oh, and we would have lost Henry VIII, too) but, in fact, we would have lost very much more than that. The First Folio didn’t just bring us those 18 plays that had been languishing away from the printing house, it brought us “Shakespeare”.

It invented the author: secured drama as a viable endeavour and a literary as well as theatrical craft and promoted the coterie of creativity that would come to define Shakespeare’s reputation as he drifted through the ocean of brilliance into the photic zone of genius.

What If…

What if it hadn’t happened? What if the First Folio was never published?

I want to imagine, if we can, a world without Shakespeare. It’s almost impossible to slip through the quantum gap and live a parallel life without the formative cultural, education, creative, political, and social practices that have shaped the worlds and times into which we are born. But let’s try.

It’s 1623 and Shakespeare’s beloved wife, Anne dies. She is survived by her two daughters, Susanna and Judith, and her granddaughter, Elizabeth. Elizabeth does not have children and the children of Shakespeare’s sister, Joan, carry the Hart line through to the 19th Century, with her son, Thomas inheriting what is now known as Shakespeare’s Birthplace. But without the First Folio, the Birthplace could well have not been maintained, and probably have gone through many iterations or even not exist as a building at all.

So, in our world without Shakespeare, we’ve also lost a part of what makes Stratford-upon-Avon so meaningful to people from across the globe, along with the clever, and sometimes funny shops and cafes whose names lovingly reference the plays found in the First Folio. We’ve also lost theatres and festivals across the world who have focused on Shakespeare’s work. Without the First Folio would we have the Globe or the RSC in the UK? Would we have Shakespeare’s in the Park in New York City or across North America? Probably not.

But what about in between? How might the work of James Joyce, John Keats, Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, Aimee Cesaire, Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, George Elliot, Virginia Woolf, Angela Carter, Maggie O’Farrell evolved without Shakespeare?

The impact is unquantifiable, because his influence immeasurable. It extends to all sectors of society, including politics, education, economic and social mobility as well as the creative and cultural foothold that Britain has sustained and maintained on the basis of its colonial exports and cultural identity. If we weren’t, for example, crying God for Harry and Saint George, might we be thinking differently about ourselves as a nation state? Might Boris Johnson and Keir Starmer import another worthy into their political pageants?

Who would have stepped into those giant feet of clay? And how would they have shaped our national identity?

Shakespeare is, of course, fascinated by the ‘what ifs’: what if Friar Lawrence’s letter had got to Romeo in time? What if Edmund’s message had reached the jailors of Cordelia? What if Emilia hadn’t given the handkerchief to Iago? What if Hamlet had made up his mind…. There are moments and then there are archaeologies in which a different road, response, outcome would have changed everything? That’s the definition of tragedy: it could have been different. So, a world without the First Folio would have been a tragic one. As Pericles, unrepresented in the Folio, would have it: ‘To hear the rest untold, sir, leads the way’.

So in our quantum alternative, without the First Folio, we have lost a lot: we’ve lost a lot more than those 18 plays: we’ve also lost Hamlet, the skull, the currently best description of suicidal ideation in the vernacular, we’ve lost stories of power, empathy, of wanting to be elsewhere, another body, a different mind; we’ve lost the hope of a happy ending and the image of that horror. Perhaps, above all, we’ve lost the permission to think in the margins: to consider the silences, the problems, the gaps, as Gower would have it, that stand in the stages of our history and where Shakespeare shouts loudest is at the critical point when you are lost for words: for sympathy, for representation for that Friday night when ‘hell is empty and all devils are here’.

So, 2023 is not just about what we would have lost, it’s also about what we’ve gained. Shakespeare has given us problems, he’s given us answers: his work has supported the powerful and the oppressed, the marginalised and the unforgiven. He’s led from the front and from behind: he’s soft and he’s hard power: but what the legacy of 1623 really gave us was a version of our realities that we can keep reinventing: for better and worse, he shines like a good deed in a naughty world, but to paraphrase Beccy Helmsley, we can’t spread the light if we’re all burnt out. So, maybe, just maybe, Shakespeare can keep us shining.

Professor Charlotte Scott is Director of Knowledge at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.