When thinking of a name for our new blog series, the first Shakespearian character that came to my mind was Prospero. In Act 1, Scene 2 of The Tempest, Prospero says to Miranda: “Me poor man, my library was dukedom large enough.” After losing his dukedom, all Prospero is left with are his books. For him, the real treasures are learning and books. I couldn’t agree more with Prospero. The best part of my job is working with an amazing book collection, filled with treasures.

The library of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust not only provides a source for learning but also contains surprises, secrets and stories. Comprising 55,000 books including 3000 rare and early printed books, The Trust’s book collection is a true treasure trove for the human inspiration.

To give you a flavour of our library holdings, I have compiled a list of quirky facts relating to our most unusual and significant books.

1. The Folios. These are our early Shakespeare editions, the first of these was published in 1623, the second in 1632, the third in 1664 and the fourth in 1685. The Trust looks after seventeen Folios in total.

2. One of the Trust’s First Folios was washed in the nineteenth century. This involved taking the book apart and immersing the pages in water. Unfortunately, this practice can remove inscriptions. Not surprisingly, this First Folio is squeaky clean!

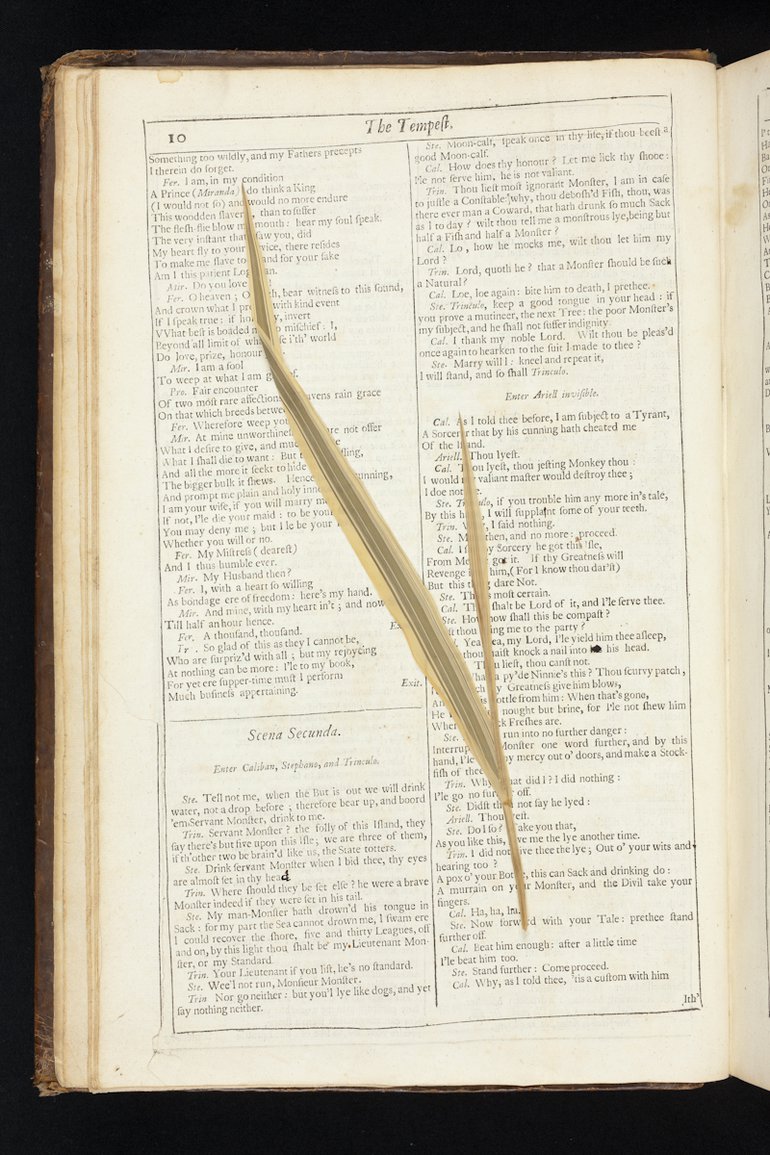

3. Our Digitisation Officer found an unusual item inside one of our early printed books, a Fourth Folio of Shakespeare’s work: a bamboo leaf! A previous owner, a hobby botanist used his or her Fourth Folio as a plant and flower press.

4. A notorious book lover and collector with the colourful name James Orchard Halliwell Phillipps used to own a First Folio, which is now in our collection. He had a most unorthodox research method: he used to cut up books, not always his own, and paste them into his notebooks. We now keep those notebooks in our rare book collection. We’re lucky that he didn’t cut up the First Folio, but he did remove the Shakespeare portrait and sold it to a book dealer in America.

5. The oldest book in our collection dates from 1520 and is titled Here begynneth a shorte and a breve tale. Also called the Saint Albans Chronicle, Thomas Walsingham, an English chronicler and Benedictine monk who lived at St Alban's Abbey authored this book. His chronicles cover the reigns of Richard II, Henry IV, and Henry V.

6. The smallest books in our library are thirty nine miniature editions of Shakespeare’s works published in Glasgow in 1904. The books’ dimensions are 5 by 3.5 cm. Shelved on a purpose built revolving wooden bookcase, they make a perfect accessory for a dollhouse!

7. This list wouldn’t be complete without our largest books, which Trust staff refer to as the ‘American’ book. It is so big that we have to store it flat on the work top surface in one of our stacks. Its unofficial title comes from the fact that a group of American donors gave money towards the rebuilding of the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre and created this monumental book as part of their fundraising initiative. Pasted inside are hundreds of cards with the donors’ names.

8. There are over 80 languages represented in the library collection. From Afrikaans to Yoruba, our translations are evidence of the universality and enduring appeal of Shakespeare’s works around the globe. Some of our most unusual translations include Hamlet in Basque, which Elizabeth II gave to us as on a permanent loan and a Hamlet in Russian translated by Konstantin Konstantinovich, who was a relation of Russia’s last czar. To find out more about our translations, please see our Translating Shakespeare blog series.

9. Some of our books are made of unusual materials, for example a 1930 Hamlet in Spanish printed on pure cork. The book is so fragile, just turning the pages is headache inducing as this can damage the sheets. It contains 78 extremely thin and light leaves that have decorative borders illustrated by Anthony Salo. Only 100 copies exist worldwide.

10. Our holdings are particularly rich in illustrated editions of Shakespeare’s works. His plays and poems have provided an endless source of inspiration for visual artists and our library is testament of this: we look after illustrated editions by Henry Moore, Picasso and Salvador Dali.

11. The list has to finish with one of my favourite items, a fore-edge painting. I discovered one of our three fore-edge paintings while browsing a book, looking for something entirely different. When I inadvertently fanned the pages, a visual feast was unveiled before my eyes: a painting applied on the edges of the book, showing the river Avon in the foreground and Holy Trinity in the background. The art of fore-edge painting has quite a long history and began when librarians shelved books with the fore-edge facing the reader. They used this part of the book for identification by inscribing the fore-edge with the book’s shelf mark or author and title. The first fore-edge paintings were painted on the outer edge of the pages, making the painting visible when closed. Over time artists discovered how to hide their artworks by fanning the pages and painting on the slight inner edges and gilding the outside page edges afterwards. Thus the painting remains hidden while the book is closed and is only revealed when you fan the pages.