This blog about Edward Topsell's The History of Foure-Footed Beasts is from Victoria Jackson, Doctoral Candidate in the History Department, University of Birmingham.

When the ghost of Banquo appears in Macbeth’s seat at the table in the ill-fated banquet scene, Macbeth is so frightened that he pleads with him to appear in any other form:

‘Approach thou like the rugged Russian bear,

The arm'd rhinoceros, or th'Hyrcan tiger’

(Macbeth Act 3, Scene 4).

But when Macbeth was first performed in 1606, how would an audience have understood these animals or pictured the physical characteristics that gave them a fierce or wild appearance? Most Jacobeans would never have seen a rhinoceros in the flesh, so what did they think of when they heard the words ‘arm’d rhinoceros’? One way people encountered these exotic animals was through books. ‘Bestiaries’, for example, were illustrated volumes of detailed descriptions of every known creature in the animal kingdom.

A year after Macbeth’s first performance, an English clergyman named Edward Topsell (1572-1625) published The Historie of Foure-Footed Beastes, a hefty treatise on zoology running over 1,000 pages. In 1608, Topsell published The History of Serpents and both volumes were later released together in 1658 as The History of Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents.

The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust has a copy of Topsell’s compendium of the animal world within its impressive collection of early modern books. Foure-Footed Beasts features a series of vibrant woodcut images of both real and mythical creatures. A grazing gorgon is depicted on the title page, here shown as a scaly pig with a mop head of hair. A gorgon was also evoked when MacDuff likens looking upon the murdered body of King Duncan to:

‘destroy[ing] your sight with a new Gorgon’ (Macbeth Act 2, Scene 3).

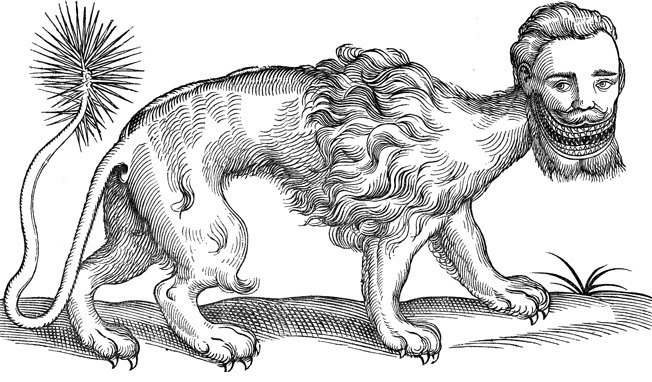

Topsell also includes the legendary ‘manticore’, a creature with the body of a lion and head of man, which was said to bear such a wide grin, you could see its three rows of razor-sharp teeth.

Perhaps the most blood-curdling animal Topsell writes about was the legendary lamia, a scaly creature with the hind legs of a goat, fore legs of a bear and the chest and head of a woman. Topsell states that when a lamia sees a man they ‘lay open their breastes, and by the beauty thereof, entice them to come neare to conference, and so having them within their compasse, they devoure and kill them.’ (p.455)

Topsell seems quite certain that these creatures really existed, although he does express doubt over the existence of the ‘hydra’, a many-headed serpent that was killed by Hercules as the second of the Twelve Labours. But alongside these, his volume illustrates everything from house cats, giraffes, beavers and rhinoceroses. The rhinoceros portrayed in Foure-Footed Beastes was derived from an earlier woodcut by the German printmaker Albrect Dürer, who based his image on written descriptions of an Indian rhinoceros owned by the King of Portugal in 1515. He depicts the rhinoceros with hard plates that cover his body like sheets of patterned armour and a solid-looking breastplate and is reminiscent of Macbeth’s ‘arm’d rhinoceros’. Dürer’s rhinoceros became one of the most popular animal images throughout Europe and for the next 300 years illustrators continued to borrow from his woodcut.

Topsell appropriated a lot of his material from other zoology texts, and, as he acknowledges, he draws heavily from the ‘all the volumes of Conrad Gesner’, a Swiss naturalist who wrote in the mid-sixteenth century. But Gesner and Topsell had very different intentions in producing their compendiums. Gesner was interested in providing scientific information about plants and animals to his readers, and his works are today considered the beginning of modern zoology. Topsell, on the other hand, was not an expert in zoology or natural history, but a clergyman who, alongside Four-Footed Beasts, published spiritual treatises such as The Reward of Religion (1596) and The Householder, or, the Perfect Man (1610). Throughout Four-Footed Beasts, Topsell maintains that his reader should ‘meditate’ upon these creatures as they provide moral and social exemplars for humans. He asks:

‘What man is so void of compassion, that hearing the bounty of the Bone-breaker Birde to the young Eagles, will not become more liberall? Where is there such a sluggard and drone, that considereth the labours, paines, and trauels of the Emmet, Little-bee, Field-mouse, Squirrel, and such other that will not learne for shame to be more industrious, and set his fingers to worke?’ (sig.a5r)

So rather than a book on animals for the sake of scientific interest, Topsell believed that the natural world had been arranged as it was by God in order to provide an instructive guide for humanity.

One of the most fascinating outcomes of Topsell’s book was that its accompanying woodcuts provided source images of animals for depiction in other media, such as embroidery, painting and woodworking. For example, an elm-wood box made in Southwark between 1600 and 1625 is decorated with heraldic ornament and pairs of cocks, griffins and doves derived from Topsell. You can see it in the collection of the V&A.

More recently, a history of medicine student at the University of Minnesota used Topsell’s woodcut of a satyr to carve her Halloween pumpkin!

Four-Footed Beasts represents one way in which people of the past could ‘see’ animals, which they would never have the opportunity to encounter in the flesh. But it also expresses how popular belief was articulated in everyday life through dynamic animal stories depicted in books or in household items.