The Russian Revolution is sometimes referred to as the October Uprising or Red October, as according to the Julian calendar Bolsheviks took St. Petersburg on October 25, 1917. Using the Gregorian calendar brought in by the Bolsheviks – sometimes referred to as the New Style – the date was November 7, 1917.

Shakespeare had had a long history with Russia. He had mentioned Russia in Winter’s Tale and Love’s Labor’s Lost, for example. Furthermore, his translators from English to Russian had included such notable figures as Empress Catherine the Great and Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich of Russia. These imperial ties, though, do not appear to have been held against Shakespeare come the Revolution.

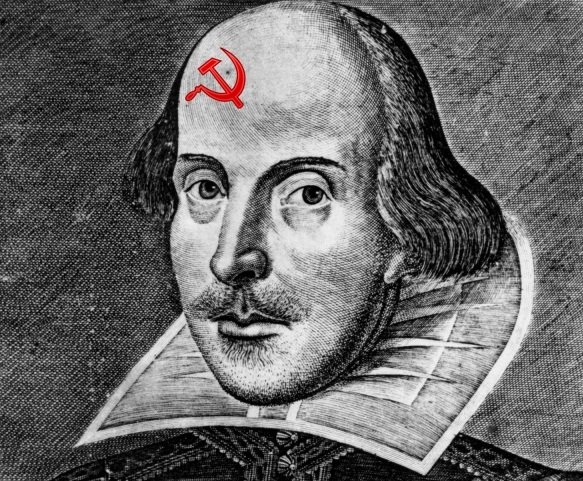

Although the rise of the Soviets in Russia spelled the doom for many authors “purged” from public libraries because of their history, their social value, or their politics, Shakespeare was more fortunate than most. Indeed, while Lenin’s wife, Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya, who served as a Deputy People’s Commissar for Education and helped design lists of censored books, banned writers such as Plato, Kant, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky, arguing both that they presented “harmful” politics and that they were “senseless” to have in a public library as “a man of the masses will not read Kant.” Shakespeare, though, would not be deemed harmful or “too elite” for the Russian public. According to Joseph G. Price, “Karl Marx had extolled Shakespeare as one of the world's geniuses.” Therefore, Shakespeare could avoid the purging that befell some authors whose work deal with complex moral questions, monarchy, or religion. Instead, he was read as speaking to the class struggle.

Lenin and his wife agreed that the communist government of Russia would need an educated Russian people. Therefore, far from banning Shakespeare, they sought to make his work more available to the working people, “extending to the proletariat the role that Shakespeare had played in educating the Russian aristocracy for two centuries.” It would seem that as the land and wealth held by the aristocracy had become available to the proletariat, so must Shakespeare. Indeed, this dissemination would be both literary and theatrical. From1917 and 1939 – which includes the years after Lenin’s death in 1924 – five million Shakespeare’s plays were published, not just in Russian but in the twenty-eight languages of the Soviet Union. Furthermore, it is estimated that in that period there were more productions of Shakespeare plays in Soviet theatres than were produced in the theatres of the United States and Britain combined. 1933 saw the empire-era Russian Theatrical Society renamed the All-Russian Theatrical Society and the establishment of their Shakespeare Cabinet, which hosted twice monthly meetings for the discussion of Shakespeare for artists and academics, as well as publishing Shakepeare-related texts, one of which is in the SBT holdings.

As happened under other despotic regimes or times of heavy censorship, people relied on Shakespeare for free expression. Both before and after the rise of the October Uprising, writers who feared their work might be subject to censorship sometimes turned their attention to Shakespeare in discussion or in translation, an approved subject matter they could use to cloak their Aesopian double-speak. Tiffany Ann Conroy Moore notes at length how Shakespeare, “an artist admired by Lenin, Marx and Engels, who had been rehabilitated in Soviet criticism” could be used as a “screen” to hide more radical politics, causing a proliferation of films using Shakespeare as an allegory for the contemporary situation. Shakespeare plays were staged in period dress to mask their contemporary relevance. In both means, those who feared a controlling regime could use the ‘pre-approved’ text of William Shakespeare to engage in sub-rosa social critique.