A vast collection of objects is listed in the ‘lower parlour’ of innkeeper Thomas Dixon’s (alias Waterman) 1603 inventory. Benches, a trestle table, a wicker chair and beds of all kinds appear within this one space. Table cloths, napkins and sheets are mentioned alongside coffers, an iron-bound chest and a trunk. Quilts, mattresses, cushions, pillows and painted cloths add to the assortment of soft furnishings. And personal possessions - a sword, a pistol, and clothes - feature beside a mass of tableware, pewter, pots and cooking implements.

The contents of Thomas Dixon’s lower parlour fill over two pages of his inventory. Each item recorded provides some clue as to the use and possible appearance of this room. But these objects also hint at the wealth and potential status of the owner. In this way, inventories help us to understand how people in the early modern period lived as well as how they used their homes. When we focus on inventories from a certain social level, these documents also shed light on the sorts of things Shakespeare may have owned and used to furnish New Place.

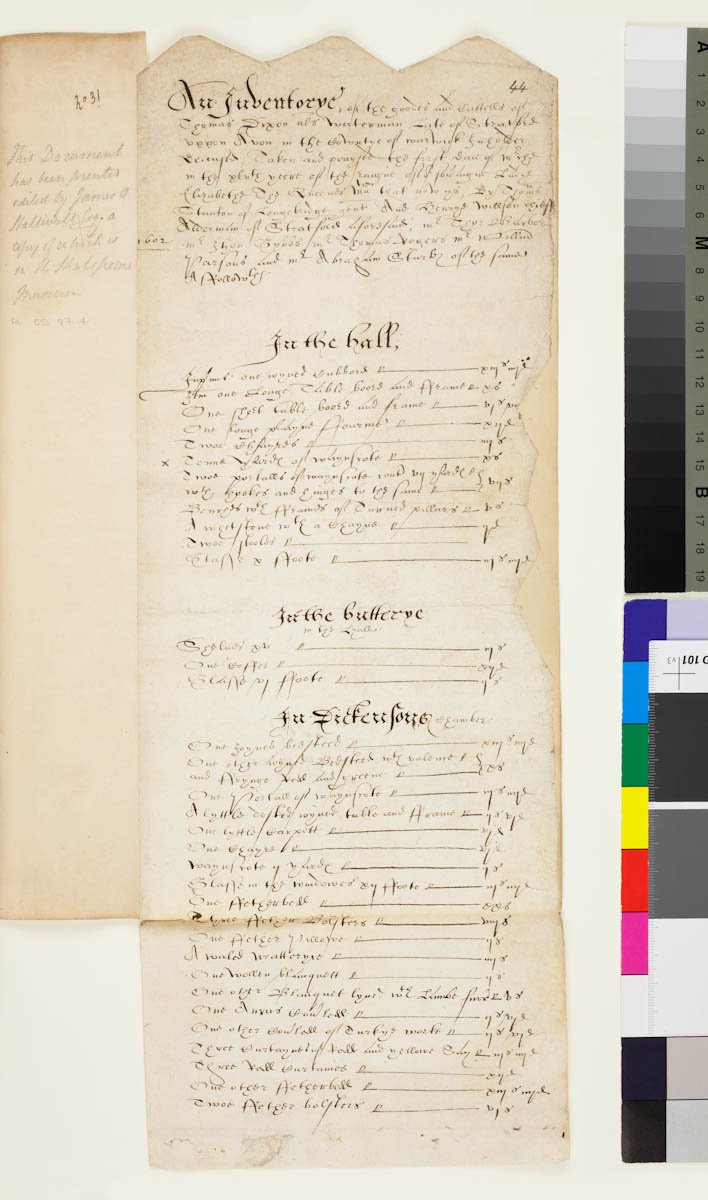

Inventories are key sources of evidence for historians studying early modern homes. They were lists of household goods and personal possessions usually made upon a person’s death. Most men (and some women) of middling status and above had one. Inventories formed part of a process called probate. This refers to the collecting together of assets (land, property and possessions) belonging to the deceased and then distributing them among their beneficiaries (family and friends for instance). Movable items were valued and listed in an inventory before being re-sold. Specific objects and assets such as land were bequeathed in wills.

Over the centuries, many inventories and wills became separated. This appears to have been the case for Shakespeare’s probate documents. A record made on 22 June 1616 (TNA PROB 8/16, fol.155r-v) tells us that Shakespeare’s son-in-law, John Hall, delivered the playwright’s will with inventory to the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PCC) in London. Wills were proved by a number of courts, but the PCC dealt with the probate of relatively wealthy people like Shakespeare. Shakespeare’s original will and the registered copy have survived, but his inventory is sadly lost. It may well have been destroyed with numerous other inventories from this period in the Great Fire of London in 1666 (A. Nelson, Shakespeare Documented: Folger Library, 2020).

The probate records of Shakespeare’s brother-in-law, Bartholomew Hathaway, remain in the care of the SBT. Bartholomew was a relatively wealthy yeoman farmer and lived in the property now known as Anne Hathaway’s Cottage in Shottery. His inventory helps us to understand more about early modern homes in and around Stratford-upon-Avon. From this document we learn that the house contained several rooms. The ground floor had a hall, kitchen and possibly a parlour. Additional chambers were positioned on the floor above and various outbuildings such as barns and a stable were located nearby. From the items listed under each room we get some sense of its use and potential decoration.

The hall was an important space for men like Bartholomew Hathaway. It had a very different function from today’s entrance areas and was usually the largest living space in the early modern home. Much like the hall displayed at Shakespeare’s Birthplace, these rooms were largely used for dining and entertaining. This is also demonstrated in Bartholomew Hathaway’s inventory:

In the hall:

One table, 2 chairs, two benches, 2 stools, 2 cushions at 10 shillings (s)

8 pieces of pewter [plates, cups etc], 1 brass candlestick, 1 chaffing dish at 10s

1 pair of links [chains], 1 pair of bellows at 2 s

2 brass pots, 2 kettles at £1 6s 8p

This collection of objects confirms that Bartholomew’s hall was almost certainly used during mealtimes. The table, seating and dining ware indicate that large, household gatherings also took place in this room. While the brass pots and kettles suggest that the space was also used for some sort of cooking.

Although we do not know the appearance, quality or condition of these objects, we can look at surviving examples to get a better idea. Chairs, similar to the armchair pictured below, were reserved for the head of the household and his most esteemed guests. They were heavy, took up a significant amount of space and encouraged a rigid posture. The upright position of the chair’s back together with its wide arms put the sitter in an especially authoritative position. Seating in early modern England was hierarchical and symbolic. What you sat on, and where, suggested your position in the household. Bartholomew Hathaway would have sat in a chair much like this at the head of the table to symbolise his authority. Important guests would have taken the other chair present. The mistress of the house may have sat upon one of the stools mentioned in the hall. And the two cushions listed would be used to add a touch of comfort as well as decoration. Other members of the household might then be permitted to sit on simpler stools or the wooden benches also provided. From these inventories, we begin to uncover information about the function and furnishing of early modern homes, as well as the experiences of the people who lived there.

These documents may provide clues about early modern interiors, but they are not completely reliable. The structure of inventories varied according to region, social status and gender. Their main purpose was to provide an index and valuation of a person’s goods and belongings. As a result the language used in these documents was often economic and not at all descriptive. The process of taking an inventory (the appraisal) was also fraught with issues. Members of the deceased’s family might move or hide certain objects before the appraisers arrived. If the inventory was taken around the time of death, or just after, prized possessions may have already been gathered together in the sick chamber. Often, a person on their deathbed wished to be surrounded by their most valued goods. As a result, objects and even large items of furniture would be moved from their usual position into the sick chamber. This makes inventories slightly misleading, especially when using them to work out which objects filled what rooms. Furthermore, a room would not be mentioned at all if it was empty at the time of appraisal, or if it was occupied by a lodger. Consequently, goods or entire rooms might be left out altogether.

Despite these challenges, inventories can be used to gain a sense of the type and variety of goods found in early modern homes. Shakespeare’s inventory may no longer survive, but we can look at inventories belonging to similar people to understand what sort of furnishings he might have had at New Place. From a simple consideration of the hall mentioned in Bartholomew Hathaway’s inventory, we discover how this space was likely used. If we match the furnishings mentioned with surviving examples, we can think about their appearance and how they were experienced by different members of the household. And if we consider these items together, we can analyse the relationship between different furnishings. Patterns begin to emerge when we consider multiple inventories side-by-side. From there, we get a real sense of Shakespeare’s own interiors. Together, material and documentary evidence provide vital pieces in the puzzle of lost homes like New Place.

Alex Hewitt is a PhD student in History at the University of Birmingham and is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council: Midlands3Cities

Transcriptions of the inventories mentioned in this article can be found in J. Jones (ed.), Stratford-upon-Avon Inventories, 1538-1699, Vol. 1, (The Dugdale Society in association with The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, 2002)

For more information on early modern inventories and their challenges see L. Orlin, ‘Fictions of the Early Modern English Probate Inventory’ in H. Turner (ed.), The Culture of Capital Property, Cities and Knowledge in Early Modern England (2002), pp.51-83