As digitisation continues this month in the studio, I have had the pleasure of working with one of the most impressive collections held at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. This collection, known to the Trust as ‘The Bram Stoker Collection’, was presented to the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in 1920 and consists of over 70 boxes of memorabilia, including caricatures, playbills, programs, personal correspondence, menus and reviews, that were once in the possession of Bram Stoker―an Irish novelist and short story writer best known today for his gothic novel Dracula―between 1878 and 1895 when he was serving as manager to Henry Irving at the Lyceum Theatre. The collection offers an incredible ‘inside look’ into Stoker’s life as a manager, the stage career of Henry Irving and also includes items and documents related to Dame Ellen Terry.

In previous posts Anna has blogged about some of the famous names that (not unexpectedly) crop up in Stoker’s personal correspondence. These have included letters from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (author of Sherlock Holmes) and Oscar Wilde. Throughout my work this month, however, I have also come across letters to Stoker from J.M. Barrie (author of Peter Pan) and a note from the famous American poet Walt Whitman acknowledging the receipt of a generous gift from Irving in 1889. Whitman was a particularly important figure to Stoker who became a life-long advocate for the poet when he first came in contact with Whitman’s controversial work Leaves of Grass at Trinity College, Dublin. Stoker did not meet Whitman, however, until March 1884 while on tour with Irving in Philadelphia. This note is a testament to Stoker and Irving’s friendship with the poet until Whitman's death in 1892.

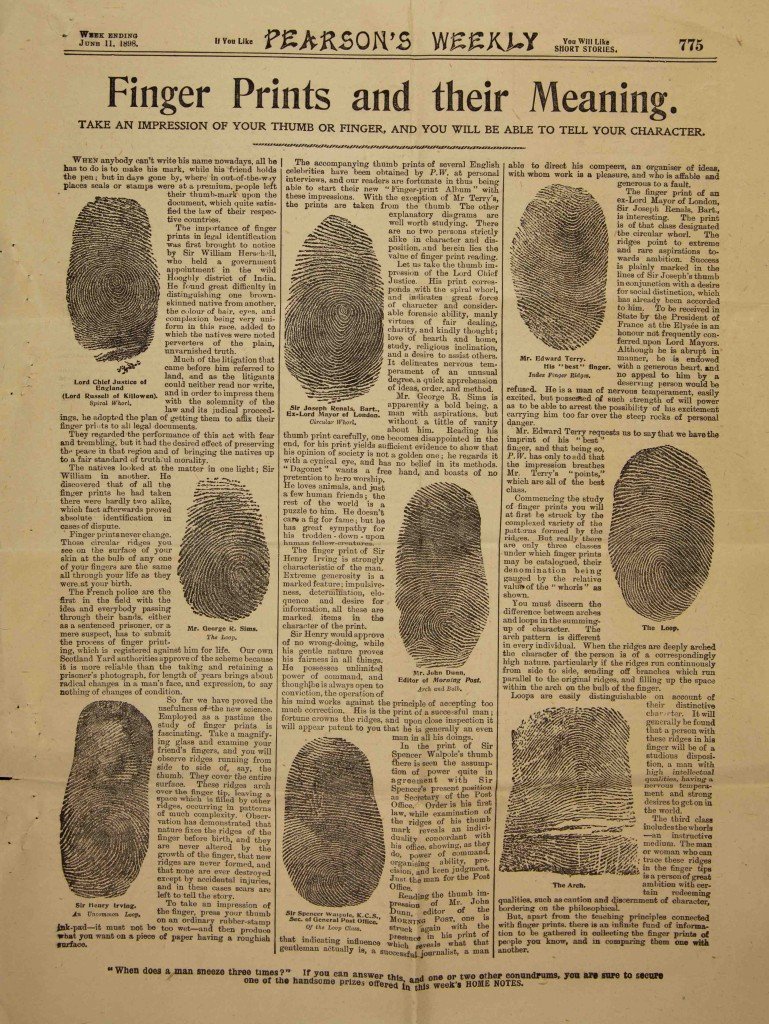

Another interesting item I have come across in the collection is a letter to Stoker from H. Onseley—a writer for the ‘Pearson Weekly’ newspaper. In his letter Onseley thanks Stoker and Irving for their troubles in providing him with Irving’s thumb print for his article ‘Finger Prints and their Meaning: Take an impression of your thumb or finger and you will be able to tell your character’. With his letter Onseley attaches the article written in the week ending June 11, 1898. The article draws upon the then new science of using finger print analysis as a form of identification― mainly in prisons and in questioning suspects. As you can gather from the title, however, Onseley takes it one step further to suggest that these prints can also tell us something of our personality and character. He gathers 9 finger prints from English celebrities in the hopes of encouraging people to begin their own ‘Finger-print Albums’. Onseley classifies Irving’s print as ‘an uncommon loop’ which suggests the following about Irving’s character:

‘extreme generosity is a marked feature, impulsiveness, determination, eloquence, and desire for information, all these are marked items in the character of the print. Sir Henry would approve of no wrong doing, while his gentle nature proves his fairness in all things. He possesses unlimited power of command, and through he is always open to conviction the operation of his mind works against the principle of accepting too much correction. His is the print of a successful man, fortune crowns the ridges, and upon close inspection it will appear patent to you that he is generally an even man in all his doings’.

Articles like these demonstrate the scope of Irving’s popularity at the end of the nineteenth-century and can show us the general public options of Irving’s character at the time. They can also be great fun, however, as I must confess I had to take my own finger print for analysis after reading it― it is almost like a nineteenth-century horoscope! Why not try it yourself? Or better yet, create your own ‘Finger-print Album’ as Onseley concludes ‘there is an infinite fund of information to be gathered in collecting the finger prints of people you know, and comparing them with each other’.