Susanna and the Elders is a story from the Old Testament book of Daniel, but is only present in the Roman Catholic and Orthodox versions. In Shakespeare’s day it was not printed in any of the Protestant bibles.

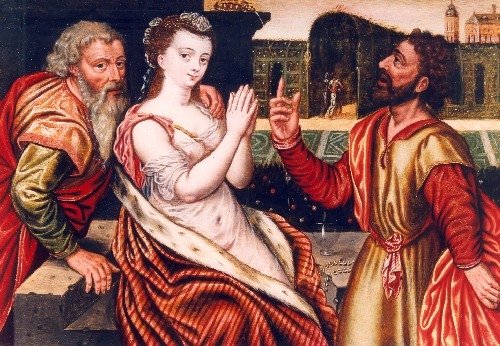

This painting captures a moment from the story. In the foreground Susanna, the wife of the wealthy Jo’akim, sits with her hands clasped in prayer. On either side are the elders who appear to be in the process of laying down their ultimatum – she must consent to commit adultery with them or they will have her put to death by telling everyone that she has committed adultery with another man. In the background two figures, perhaps Susanna’s maids, are walking out of the garden through an archway.

19 When the maids had gone out, the two elders rose and ran to her, and said: 20 “Look, the garden doors are shut, no one sees us, and we are in love with you; so give your consent, and lie with us. 21 If you refuse, we will testify against you that a young man was with you, and this was why you sent your maids away.”

22 Susanna sighed deeply, and said, “I am hemmed in on every side. For if I do this thing, it is death for me; and if I do not, I shall not escape your hands. 23 I choose not to do it and to fall into your hands, rather than to sin in the sight of the Lord.”

So Susanna calls out for her maids and the elders say that they found her in the garden with another man. The next day she is put to trial and ‘because they were elders of the people and judges’ their testimony against her is believed and she is sentenced to death. As she is being led away she prays to God to save her and this moves Daniel to stand up and say ‘I am innocent of the blood of this woman’. This, it turns out, is a preamble and he goes on to challenge the testimony of the elders and prove they are lying. It is the elders who are then sentenced to death and Susanna is pardoned.

This picture has been attributed to the school of the Flemish painter Frans Floris (1517-1570) who was born in Antwerp. At the time it was painted, around 1550, the Netherlands, a largely Protestant country, was staging an eventually successful revolt against Catholic Spain. The background of religious turmoil adds an extra depth to the choice of subject matter. Perhaps the painting was commissioned by a wealthy Catholic client eager to show support for his Church.

There is no doubt that Shakespeare was familiar with this story. In The Merchant of Venice Shylock describes Portia (disguised as a lawyer) as ‘A Daniel come to judgement! Yea, a Daniel’. This scene not only echoes the trial of Susanna but also her salvation seemingly against the odds. Both Portia and Daniel are youths but they have the wisdom of elders.

It is also interesting to consider the name that Shakespeare and Anne chose for their eldest daughter. Susanna was not a family name and was also not a common name in Stratford at the time. René Weis discusses the naming of Susanna in his book Shakespeare Unbound. The name could have been that of her Godmother, possibly Susannah Tyler (nee Woodward). This would be in line with tradition and it seems as though Judith and Hamnet were named after their godparents who were probably Hamnet and Judith Sadler. However if she was not named after her godmother it is possible that the choice of name has religious connotations. Perhaps it was an act of loyalty to the Catholic church? Weis, however, also points out that there were two other Susannas named in a period of 6 weeks in the town and both of them were from strict Protestant families.

Although we may never know it is fascinating to explore these different sources and to still be able to see such a beautiful painting created more than four hundred and fifty years ago.